(June 14, 2021) – Players from Mali’s Under-18 girls’ national basketball team have reported sexual abuse by the head coach, but the Mali Basketball Federation has failed to act on their reports, Human Rights Watch said today. Malian law enforcement should credibly and impartially investigate the allegations and protect those who reported the abuse from retaliation.

Amadou Bamba, 51, the Under-18 girls’ national basketball team’s head coach since 2016, sexually assaulted or harassed at least three players and thwarted their careers when they refused to have sex with him, survivors told Human Rights Watch.

“Many girls in Mali hoped that their talents and hard work in basketball could help them achieve their dreams to play for the national team,” said Minky Worden, director of global initiatives at Human Rights Watch. “But for many, sexual harassment and violence have been a frequent, devastating, and completely unacceptable part of their athletic experience.”

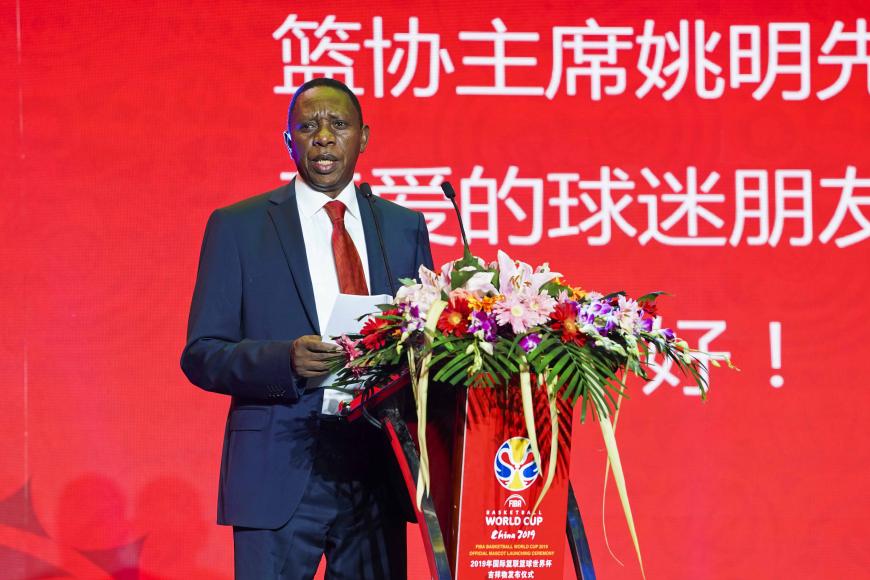

After Human Rights Watch wrote to the Fédération Internationale de Basketball (FIBA), world basketball’s ruling body, detailing the sexual abuse reports in Mali, FIBA has taken an important first step to suspend, pending investigation, coaches and officials who are alleged to have participated in or knew of the abuse. FIBA’s President Hamane Niang, the Malian leader of basketball’s governing body, has stepped aside during the investigation. FIBA should also support providing services to survivors, including counseling, health care, and legal assistance, Human Rights Watch said.

Basketball is tremendously popular in Mali, and the women’s and girls’ national teams have played in the Olympics and long been top contenders for international titles. Human Rights Watch spoke to three survivors and their family members who reported Bamba’s abuse to the Mali Basketball Federation. The federation failed to act on these complaints and tried to cover up Bamba’s abuse by promising the survivors that they would be chosen for the girls’ national team in exchange for silence.

Several of the reported abuses took place at international competitions, including the FIBA Under-19 Women’s Basketball World Cup and the FIBA Africa Under-18 Championship. The 2021 FIBA Under-19 Women’s Basketball World Cup takes place in Hungary from 7 to 15 August, where Mali is one of 16 teams competing.

In Mali, survivors and their family members reported sexual abuse by Bamba dating back to 2016, his first year as head coach. Ajara, a former player on the Under-18 girls’ national team, whose name, like others, has been changed for her protection, was sexually harassed and assaulted by Bamba, said her father, whom she told about it. He said the harassment began when his daughter, then 17, was trying out for the team: “Bamba called her and said he wanted to have sex with her, and that she would need to have sex with him to get a spot.” She refused. At an international FIBA tournament, the abuse escalated into sexual assault: “He [Bamba] came into her [my daughter’s] hotel room at 2 a.m…. He grabbed her hand, made her touch certain parts on his body. He put his hands underneath her underwear.” She ran out of the room. After the assault, Bamba significantly reduced her playing time on the team.

Two other former players on the team described similar experiences. Another player, Mariama, told Human Rights Watch that when she was 15, Bamba attempted to have sex with her in a hotel room on a team trip to an international FIBA tournament, and removed her from the team when she refused. She also said that Bamba threatened girls on the team with imprisonment if they reported the abuse. A third girl, Oumou, said that when she was on the team at age 17, Bamba tried to touch her breasts and have sex with her: “When I refused him, he didn’t let me play. He kept me out of games.”

Players told Human Rights Watch that Bamba was sexually abusing other players on the Under-18 girls’ national team, exchanging sex for playing time, money, and equipment. In Mali, indecent acts with people between 15 and 21 years old are illegal if the offender has authority over the person or if the offender is in charge of the person’s education, supervision, or employment.

The Mali Basketball Federation, as part of its oversight function and its membership in FIBA, has the responsibility to protect players from abuse, and to hold abusive coaches accountable through sanctions and removal. FIBA’s “Five Pillars of Safeguarding Rights of Children and Adults at Risk” states there is “zero tolerance” for sexual harassment and abuse of players, including the abuse of children by their coaches. Allegations of abuse must be reported to local law enforcement and to FIBA for investigation. According to FIBA policy, violations can lead to sanctioning of the national federation.

FIBA is also governed by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which prohibits child abuse and abuse of athletes in the Olympic Charter. The IOC trains international federations to recognize and combat abuse of athletes through its Safeguarding Toolkit, and has a reporting tool, but does not adequately address athletes’ safety and rights when the federation leaders or staff are implicated in or are deploying federation resources to cover up abuse.

Sexual harassment and assault have long-term impacts on survivors’ physical and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress. The father who described his child’s experience said that his daughter, a gifted player, quit playing basketball after Bamba’s assault: “She is generally withdrawn and doesn’t have anything going on right now. She was traumatized.”

Several players and their family members said that they alerted the Mali Basketball Federation to Bamba’s abuse months ago. Though the Mali Basketball Federation has oversight of the Under-18 girls’ national team, including the selection of the coach, Human Rights Watch has no information that the federation has taken action to address the reported abuses.

“Because the girls are scared to lose their spots on the team or face other consequences – it is a really difficult situation,” said Ahmar Maiga, founder of Young Players Protection in Africa-Mali. “Normally protecting players is the role of the Malian Basketball Federation, but nobody cares about the impossible situation these young athletes are in.”

Mariama said that she told the president of the federation, Harouna Maiga, about Bamba’s attempt to have sex with her, and her subsequent removal from the team. She said that Maiga offered her a spot back on the team if she did not officially report Bamba: “That’s how I got to play [in international FIBA tournaments]. The president said that as long as I didn’t disobey the coach, I could stay on the team.” The father who described his daughter’s abuse said that he reported Bamba’s abuse of his daughter to Maiga, but that Maiga had not responded.

The Mali Basketball Federation’s failure to investigate or address serious allegations of abuse pre-dates Bamba. Mariama said that Bamba is the third girls’ basketball coach with abuse allegations reported to the federation. Experts on child protection in Mali said that harassment and assault in girls’ basketball has been a serious problem for years.

Sexual and gender-based violence is a widespread problem in Mali, beyond the world of sports. A 2018 National Institute of Statistics survey found that nearly half of Malian women and girls between the ages of 15 and 49 had experienced gender-based violence.

All institutions with jurisdiction, including the Malian judiciary, the Malian Ministry of Youth and Sport, the Mali Basketball Federation, and FIBA should investigate the allegations against Bamba, Human Rights Watch said. The Youth and Sport Ministry should form a government commission of inquiry to investigate systemic sexual abuse in girls’ basketball and other girls’ sports in Mali. They should also act to ensure that players do not face retaliation for making complaints, and work with women’s rights and healthcare providers with expertise in sexual abuse and trauma so that survivors have access to long-term, quality support services.

Over the previous two years Human Rights Watch has also documented the abuse of child athletes in Haiti, Japan, and Afghanistan.

“Sports should not be a closed circle where girls are sexually harassed, punished for reporting, and then lose their ability to play a sport they love,” Worden said. “With the Japan Olympics and the FIBA Under-19 Basketball World Cup fast approaching, FIBA and the IOC need to act quickly to remove any abusive coaches and all basketball leaders who failed in their duty to protect Mali’s female players.”

For detailed accounts by the survivors and witnesses, please see below.

Accounts by Former Players

Mariama, Former Player on Coach Amadou Bamba’s Under-18 Girls’ National Teams

Mariama said that she has been playing basketball since she was 8. When she was 15, she was selected to play for Mali in an international FIBA tournament. While traveling to play in this tournament, Bamba invited the four youngest players on the team to come individually to his hotel room, to meet with them to provide “advice” about their future. “He invited us one by one, allegedly to give advice, but really it was to take advantage,” Mariama said.

She was the last of the four young players to be invited to Bamba’s hotel room. She had heard that he had tried to kiss one of the girls. When Mariama went to his hotel room, Bamba tried to force her to have sex with him, promising her money and playing time. She refused, ran out of the room and slammed the door. “He was extremely angry,” she said. “So, he took me off the team.”

Mariama went to the president of the Mali Basketball Federation, Harouna Maiga, to tell him about Bamba’s attempt to have sex with her, and his keeping her off the team as punishment. Instead of investigating Bamba, Maiga protected him. “I didn’t talk about the harassment at the time it was happening,” Mariama said. “But afterwards, I went to see the Federation president to talk about Bamba. The president said I could be on the team if I didn’t report Bamba. That’s how I got to play [in international FIBA tournaments]. The president said that as long as I didn’t disobey the coach, I could stay on the team.”

Back on the team, Mariama traveled to another FIBA tournament, staying at a hotel. Mariama reported that Bamba again targeted the youngest players on the team for sex, some of whom turned to Mariama for advice. “Coach Bamba often went into girls’ rooms, when they weren’t there or when they were alone, to go say bad things and try to make advances,” Mariama said. Some players also attended the school at which Bamba teaches. Mariama said, “The youngest were the victims. He started to harass them in school. Team members had to help younger girls to refuse his advances. He kept trying to touch the younger players’ breasts and other intimate parts.”

Mariama said that Bamba threatened girls and their families if they talked to anyone about the abuse: “Bamba tells the girls that he will imprison them and their parents because he has power. The majority of girls refuse to talk because of this. We had planned that if he didn’t stop, we would tell the federation to find a solution. We didn’t end up telling the federation, because the girls’ basketball careers were threatened.”

Naby, Father of Ajara, FormerPlayer on the Under-18 Girls’ National Team

Naby said that his daughter Ajara has been playing basketball since she was 7. By the time she was a teenager, Ajara was selected for the Under-16 and then the Under-18 Mali Girls’ National Basketball team.

Bamba’s harassment began when Ajara, then 17, was still trying out for the Under-18 national team. Bamba attempted to coerce her into having sex with him in exchange for a spot on the team. Naby said: “Bamba called her and said he wanted to have sex with her, and that she would need to have sex with him to get a spot.”

During team travel to a FIBA tournament, Bamba went into Ajara’s hotel room and sexually assaulted her. Naby said: “He [Bamba] came into her [his daughter’s] hotel room at 2 a.m. He asked her to initiate things. She was refusing. He grabbed her hand, made her touch certain parts on his body. He put his hands underneath her underwear.” Ajara managed to text a friend on the team, who came to the door and pulled her out of the room.

After this sexual assault, Bamba punished Ajara with reduced playing time. Naby said, “Bamba is the one who chooses who plays and who doesn’t. We noticed that after she refused, he didn’t let her play as much. He told her at some point that if she refused, she wouldn’t get to play as much. She didn’t care, she wasn’t going to do it.”

The experience was very traumatizing for Ajara, and she quit playing basketball. Naby said, “She was generally withdrawn, doesn’t have anything going on right now. She was traumatized. She didn’t want to play basketball anymore.”

After Bamba sexually assaulted Ajara, Naby went to the president of the Mali Basketball Federation, Harouna Maiga. But the federation has not taken any action. “I think the National Federation does know what’s going on with Bamba,” Naby said. “I called Maiga a little more than a month ago, he said he would call Bamba and ask him if it was true and tell him it was wrong if he was doing that. Maiga said he would get back in touch with me, but I haven’t heard back for a month.”

Oumou, Former Player on the Under-18 Girls’ National Team

Oumou played on the Mali Under-18 girls’ national team under Bamba when she was 17. She described sexually abusive behavior by Bamba. Oumou said that she observed Bamba “touching girls all the time. He was dating girls on the team, and touching the breasts of girls on the team … He wanted us to go out with him, sleep with him. I believe he was having sex with some of the players.”

Oumou also described being punished by Bamba for refusing his sexual advances. “When I refused him, he didn’t let me play. He kept me out of games,” she said.

Aïssata Tina Djibo, former Women’s National Team player who went on to a career in Europe and now runs Association D’aide et Accompagnement Physique, a sports reform organization in France that is focused on child athlete protection in Mali)

“I started playing basketball very young. I was always a really good player, but I struggled a lot because the coach would propose things to me that I didn’t accept. When the coach pressures us for sex, it affects your studies, your whole life.

“The victims are not speaking up because they’re scared of losing their position on the national team. And there’s the passion for basketball that they have. Everyone knows that once you’re on Mali’s national basketball team, that’s something to be extremely proud of. For you and your whole family. And it’s so important for your career. These girls have had amazing careers and they’re scared to lose their spot on the team.”